20 – November 2019

clustered | unclusteredThink of England (1999)

Martin Parr

This cluster is the second of a four-part publication series which derives from COLLATERAL's symposium ‘State of the Union’ that took place in Hasselt on the 3rd of May, 2019

a

clustered | unclusteredPatriotism as Last Refuge? A Response to Martin Parr’s Think of England in Brexit times1

Janine Hauthal

In the summer of 1998, 18 years before a slight majority of the British voted to leave the European Union, celebrated British photographer Martin Parr travelled around England,2 armed with a camera, seeking to define Englishness by encountering the nation’s people. His journey resulted in the 49-minute documentary Think of England, produced by Mosaic Films and shown as part of the BBC’s Modern Times series (27 April 1999). Throughout the film, we repeatedly hear Parr asking his interviewees how they define Englishness, what it means to be English, and whether they think that there is a difference between Britishness and Englishness. It is hardly surprising for such spontaneous chance encounters that the answers Parr receives often start with a baffled silence or slightly ashamed “I don’t know” (01:35-02:07)3 before the interviewees resort to one or other national and often also gendered cliché to typify themselves as English. A woman in a shop in Liverpool, for instance, laughingly describes herself as an “English rose”4 (36:17), while some well-off gentlemen at Henley suggest that Englishness means “doing all the right things” (03:10) or “knowing how to behave” (04:10). Other answers echo the infamous ‘Britain first’, recently revived in Brexit campaigns, as evidenced by the Rolls-Royce owner who demands that one sticks to what’s genuine, i.e. that one should not allow German motors in British cars (cf. 5:00-5:28). Some interviewees, such as the old man and his son eating a sandwich in a car in a motorway service area (16:50-18:52), refer to Enoch Powell and reveal openly xenophobic ‘send them back’-attitudes, which contrast sharply with the female walker who accepts Britain’s multicultural society with open arms (18:58-19:40).

British Euroscepticism: Defining Englishness

The initially unknowing reactions to Parr’s questions echo statements like that of historian Bill Schwarz, who described Englishness as “an indefinable matter of being, incapable of systematic explanation”.5 Or, they may illustrate the often-quoted dictum of sociologist and cultural theorist Stuart Hall, who wrote in 1991: “To be English is to know yourself in relation to the French, and the hot-blooded Mediterraneans, and the passionate, traumatized Russian soul. You go round the entire globe: when you know what everybody else is, then you are what they are not.”6

Strikingly, the people in front of Parr’s camera frequently express a reluctance to leave their island. The majority prefers to holiday in Britain and defy the bad weather (and this is just one of several instances where the documentary foregrounds facets of Englishness that have become a cliché). As the couple in the Bed & Breakfast in Weymouth enjoying their Sunday roast confesses: neither have they ever been abroad nor are they curious to go there in the future; they prefer their “good old English food that doesn’t upset your stomach” (16:54). Or as the man renting out trampolines to children at the seaside puts it: Spain to him equals sleepless nights and food poisoning (cf. 30:00-31:58).

Indeed, as European Studies scholar Menno Spiering argues, British Euroscepticism differs from that of other EU countries in that it is characterised by a strong cultural component and rests on the long-established tradition of contrasting the British Self with the European Other. According to Spiering, British Euroscepticism therefore encompasses more than a rejection of EU regulations and the ‘dictates of Brussels’; it is not just about the EU, it is about feeling deeply un-European.

Perceptions of identity are formed by means of oppositional thinking, by contrasting the Self with the Other. The British are not French, the French are not German. The case of Britain is special in that the Other can also be Europe. The Europeans are either viewed en masse as non-British, or one nation is made to represent Europe as a whole.7

Hence, while Euroscepticism is part of a wider set of dynamics across Europe, British Euroscepticism is largely defined by cultural exceptionalism and, as such, it becomes an expression of national identity. In other words, opposing Europe contributes to the formation of British national identity.8

Curiously – given Spiering’s remarks –, in her Conservative conference speech from 5 October 2016, then British Prime Minister Theresa May did not exploit British Euroscepticism in order to promote her narrative of a new united Britain.9 Instead of contrasting the British Self with a European Other, May’s argument was directed inward and focussed on the call for change within British society and democracy. Hence, even though British Euroscepticism draws attention to Europe’s continuing significance as ‘Other’ in Britain’s national narrative, its explicatory potential for the ‘Brexit vote’ is clearly limited. Thus, instead of looking across the Channel and reflecting on Britain’s relationship with Europe, it may be more constructive for an understanding of the Brexit vote to look inside, look back and ‘think of England’, just like Parr’s documentary suggests, and try to trace the possible roots of contemporary sentiments.

Fissures across England, 1999/2016

When looking at Parr’s film from the perspective of our Brexit times, one of its most striking aspects is that, on the whole, people are remarkably optimistic, happy and proud – which contrasts sharply with the feelings of anger, frustration, and depression that both Leavers and Remainers voiced before and after the referendum.10 In the documentary, one interviewee ascribes this general optimism to Labour’s victory: In the year before Parr shot his documentary, Tony Blair’s New Labour had won the elections (06:11-07:06), and that political landslide was followed by a period of increased pride in the culture of the UK, culminating in what is often referred to as “Cool Britannia”. While the phrase is a pun on the title of the patriotic British song “Rule Britannia”, “Cool Britannia” is connected with youth culture, namely the success of Britpop and musical acts including the Spice Girls, Blur and Oasis but also that of fashion designers and London’s booming house scene. Parr, however, shot most of his documentary outside of London, in more provincial locations, including Whitchurch (on the Northern border to Wales), the seaside town of Weymouth (in Dorset in the South), Bristol (Parr’s hometown), and Blackpool (in the North-West). Maybe it is by focussing on these more peripheral locations that some fissures – including class divisions, geographical differences (North – South, urban – rural areas), economic decline, decrease of social cohesion – can be felt in Parr’s film despite its overall humorous tone and feel-good attitude. In the following, I will identify four aspects which anticipate, or point to, fissures, and explore their continuities with the debates surrounding the Brexit vote.

First of all, the documentary thematizes class differences, as can be seen early on. The film begins with a shot that zooms into a pub where a crowd watches a football match, cheering ecstatically when their team wins (00:00-00:28). The cheering can already be heard in the deserted street that first comes into view. A few minutes further into the film, Parr is talking to representatives of the British upper class who explicitly and repeatedly exclude hooliganism and football-fandom from their definitions of Englishness (03:08; 03:53). Hence, the documentary draws attention to oppositional stances that reflect the British class system through the technique of juxtaposition. Indeed, class differences also played a role in the debates surrounding Brexit, for instance, in Farage’s anti-establishment campaign11 and in May’s condemnation of “citizens of nowhere” and her attempts to fashion herself as a spokesperson for “the people”.12

Secondly, the documentary also reveals inner-British divisions. In the section filmed in the North, regional differences between North and South are evoked by the man in the pub who claims that “as a race, we in the North are far more superior [sic] to the English we see in the South” but eventually admits the Henley couple he met on holiday the other day turned out to be “great people” (37:40-38:48). In addition, the scene, in which a group of youths complains that they have nowhere to hang out after the last café in town closed (26:30-27:29), hints at the differences between metropolitan urban and rural areas in decline – a difference that is also reflected in the regional divisions in the Brexit vote.13

Thirdly, in spite of the pervasive cheerfulness of the documentary, a sense of decline and poverty also emanates from the scene in which an old couple shops in a bare supermarket (36:30-36:59) as well as from the encounters with the male walker who has recently been made redundant (32:20-33:25) and with the man who cannot afford to go abroad (17:05-17:10). These scenes resonate with the frustrations of the people who feel that the UK – as a society, economy and democracy – “works well for a privileged few, but not for them” (as Theresa May puts it in her Conservative conference speech14). These frustrations may provide one of the more suitable explanations for the referendum outcome on 23 June.

Fourth and finally, one of Parr’s recurring questions throughout the documentary is whether people think England has changed. Even though most people answer in the affirmative, only very few explain the reasons behind their answer. One of the most articulate answers in this respect is given by the man trimming his hedge in a suburban neighbourhood of Bristol who bemoans the general decline in community spirit and elaborates how people are less and less in contact with one another – partly because people need each other less than before since they can buy everything in a shop (28:57-29:57). Here, Parr’s documentary is astonishingly anticipatory of the Brexit vote if we think of the post-referendum revelations about social media’s isolating and damaging impact on real-world communities (and the (ab)use of social media by the Vote Leave campaigners)15 and the widely-discussed assumption that social media’s creation of unconnected bubbles has contributed to the emergence of a post-truth era.16

Thinking of England in Technicolour – Comparing the Aesthetics of Film and Photo Series

In concluding, I would like to briefly focus on the film’s aesthetics and on how it differs from Parr’s photographic work. A closer look at both film and photographs reveals that there is a noticeable difference in framing. The two examples below (Figure 1 and 2), for instance, demonstrate how Parr often opts for odd and striking angles and partly obscures people in his photographs. This way of framing draws attention to the photographer as a shaping force guiding our viewing experience. The framing and the clearly marked composition of the photos also add a sense of irony.17

The photographs’ saturated colours, reminiscent of early film’s technicolour as well as polaroid snapshots, can be linked to the content of the photographs, namely the eccentric habits of the English people depicted by Parr. The film, by contrast, trades the photographs’ exaggerated colours and clearly marked sense of composition for generally more subdued colours, spontaneity, authenticity and fun. In the film, interview situations, in which interviewees are clearly visible, alternate with shots that resemble the photographs. Also, the sense of a journey which allows the documentary to display a variety of ‘Englands’ provides a different and more realist structure than the theme-based arrangement of Parr’s photographic exhibitions, bearing titles such as “Suited and Booted”, “Bad Weather”, “Food”, “The Cost of Living”, and “Common Sense”.18 Consequently, the film’s sense of irony is more remote than that of Parr’s photographic work. At first, this may be considered a shortcoming of the film. Yet, from a post-referendum perspective in particular, may not the film – rather than the ironic and ultimately endearing photographs – provide the more accurate portrayal of what, nearly 20 years later, has turned the UK into a deeply divided country in crisis? After all, the serial structure unites snapshots of daily life in the UK under one thematic heading, thus exhibiting more strongly a (= Parr’s) view on Britain than a view of Britain. The common denominator of the heading suggests a set of shared traits and indicates how the photographer engages with the national imaginary of the British. The documentary, by contrast, rather assembles vignettes, and the loose succession of scenes as well as the film’s open-endedness make for an ultimately less homogenizing structure. Interestingly, in the film, the premonitory fissures resulting from class divisions, geographical differences, economic decline and a decrease of social cohesion – four aspects which later presumably informed the British Brexit vote – are not visually revealed but verbally, i.e. in the statements of the people Parr encountered on his journey. Hence, it is precisely by considering the interplay of themes and composition, of moving images and speech, of individual scenes and overall framing, that the anticipatory potential of Parr’s film begins to show.

Notes

- 1While working on this article, the author received funding by the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO).

- 2Parr’s travels can be linked to the tradition of the ‘home tour’, which emerged in the 18th century as domestic alternative to the ‘grand tour’ through Europe and, together with the travel writing of the period, “permitted – indeed reinforced – the illusion of national unity” (Doris Feldmann, “Economic and/as Aesthetic Constructions of Britishness in Eighteenth-Century Domestic Travel Writing”, Journal for the Study of British Culture, Vol. 1-2 [1997], 31-46, here: 31; see also Birgit Neumann, Die Rhetorik der Nation in britischer Literatur und anderen Medien des 18. Jahrhunderts [Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, 2009], 148-165).

- 3Here and in the following, quotes from the film are my transcriptions; time indications refer to www.youtube.com/watch?v=lAgUpTxoR3Q.

- 4The expression ‘English rose’ has a long tradition within English symbolism and national typologies of feminine beauty, cf. e.g. Stephen Gundle, “The ‘Bella Italiana’ and the ‘English Rose’: Reflections on Two National Typologies of Feminine Beauty”, Manfred Pfister and Ralf Hertel (eds.), Performing National Identity: Anglo-Italian Cultural Transactions (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2008), 137-155.

- 5Bill Schwarz, “England in Europe: Reflections on National Identity and Cultural Theory”, Cultural Studies Vol. 6 (1992), 198-206, here: 202.

- 6Stuart Hall, “The Local and the Global: Globalization and Ethnicity”, Anthony King (ed.), Culture, Globalisation and the World-System: Contemporary Conditions for the Representation of Identity (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), 19-39, here: 21.

- 7Menno Spiering, A Cultural History of British Euroscepticism (Houndmills, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 2015), 20.

- 8This argument can be extended to early 20th-century British ‘fictions of Europe’ (cf. Jopi Nyman, Under English Eyes: Construction of Europe in Early Twentieth-Century British Fiction [Amsterdam/Atlanta: Rodopi, 2000]). As my current research project sets out to demonstrate, pre-referendum contemporary British literature about Europe, by contrast, is comparatively more inclined to imagine Britain in Europe (cf. Janine Hauthal, “‘No Border Can Hold Him’ – Transnational Discourses in Contemporary British Spy Novels about Europe”, Dagmar Vandebosch and Theo D’haen (eds.), Literary Transnationalism(s) [Boston: Brill, 2019], 145-157; “‘Provincializing’ Post-Wall Europe: Transcultural Critique of Eurocentric Historicism in Pentecost, Europe and The Break of Day”, Journal of Contemporary Drama in English, Vol. 3, No. 1 [2015], 28-46).

- 9Cf. “Theresa May’s keynote speech at Tory conference in full”, The Independent, 5 October 2016, n. p.

- 10Note, however, that, in an online review for the British Film Institute, Joe Sieder already described the “eccentricities and casual bigotry of England’s white ‘moral majority’” exposed in Parr’s documentary, as “a symptom of pathological self-delusion, patriotism as the last refuge of a nation”.

- 11During the Brexit campaign, for instance, the then UKIP-leader had claimed: “When you challenge the establishment in this country, they come after you, they call you all sorts of things” (Farage qtd. in “Nigel Farage’s ‘vile’ anti-immigration poster criticized: ‘Breaking Point’ advert has been reported to police for alleged racism”, The Irish Times, 19 June 2016, n. p.

- 12“Theresa May’s keynote speech”, n. p.

- 13Cf. Arnau Busquets Guàrdia, “How Brexit vote broke down: A visual guide to Thursday’s EU referendum”, Politico, 24/25 June 2016, n. p.

- 14“Theresa May’s keynote speech”, n. p.

- 15Cf. Carole Cadwalladr, “The great British Brexit robbery: how our democracy was highjacked”, The Guardian, 7 May 2017, n.p.; Mark Scott, “Cambridge Analytica did work for Brexit groups, says ex-staffer”, Politico, 30/31 July 2019, n.p. The Cambridge Analytica hacking scandal equally informs the Netflix documentary The Great Hack (directed by Karim Amer and Jehane Noujaim, released on 24 July 2019) as well as the television drama Brexit: The Uncivil War (written by James Graham, directed by Toby Haynes, released on 7 January 2019 on Channel 4) with actor Benedict Cumberbatch in the role of Dominic Cummings, the Campaign Director of Vote Leave.

- 16Ralph Keyes, The Post-Truth Era: Dishonesty and Deception in Contemporary Life (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2004). See also James d’Ancona, Post Truth: The New War on Truth and How to Fight Back (London: Ebury, 2017), 116-123, and the chapter on social media in James Ball, Post-Truth: How Bullshit Conquered the World (London: Biteback, 2017).

- 17Critics have frequently observed Parr’s sense of irony, cf. e.g. Stephen Dawber, “Martin Parr’s Suburban Vision”, Third Text, Vol. 18, No. 3 (2004), 251-262; Merle Tönnies, “Foregrounding Boundary Zones: Martin Parr’s Photographic (De-)Construction of Englishness”, Robert Burden and Stephan Kohl, Landscape and Englishness (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2006), 225-242.

- 18Cf. www.martinparr.co.uk/think.htm.

b

clustered | unclusteredEngland, I loved you

David Clarke

in your verdant years of nostalgia, cloud-harassed

and pungent, a smokestack and chippy in every gulp

of your air. In your talking-shops, your secure

institutions, you’d drink me under every table

you’d carved from the bones of your forests,

bewitch me with your blather of moderate socialism,

the pout of your lovelies in those red-tops

on mornings of damp and desperation.

Now you abandon me to stalk your ghost towers,

shrug me off as a hedge fund jettisons acres

of brownfield, as a state outsources its grief to the lowest

bidder. I only hurt you now so you’ll see me again.

c

clustered | unclusteredRule, Britannia!

Britannia, rule the waves.

Britons never, never, never shall be slaves.

FROM THE WORKS OF JAMES THOMSON, 1763

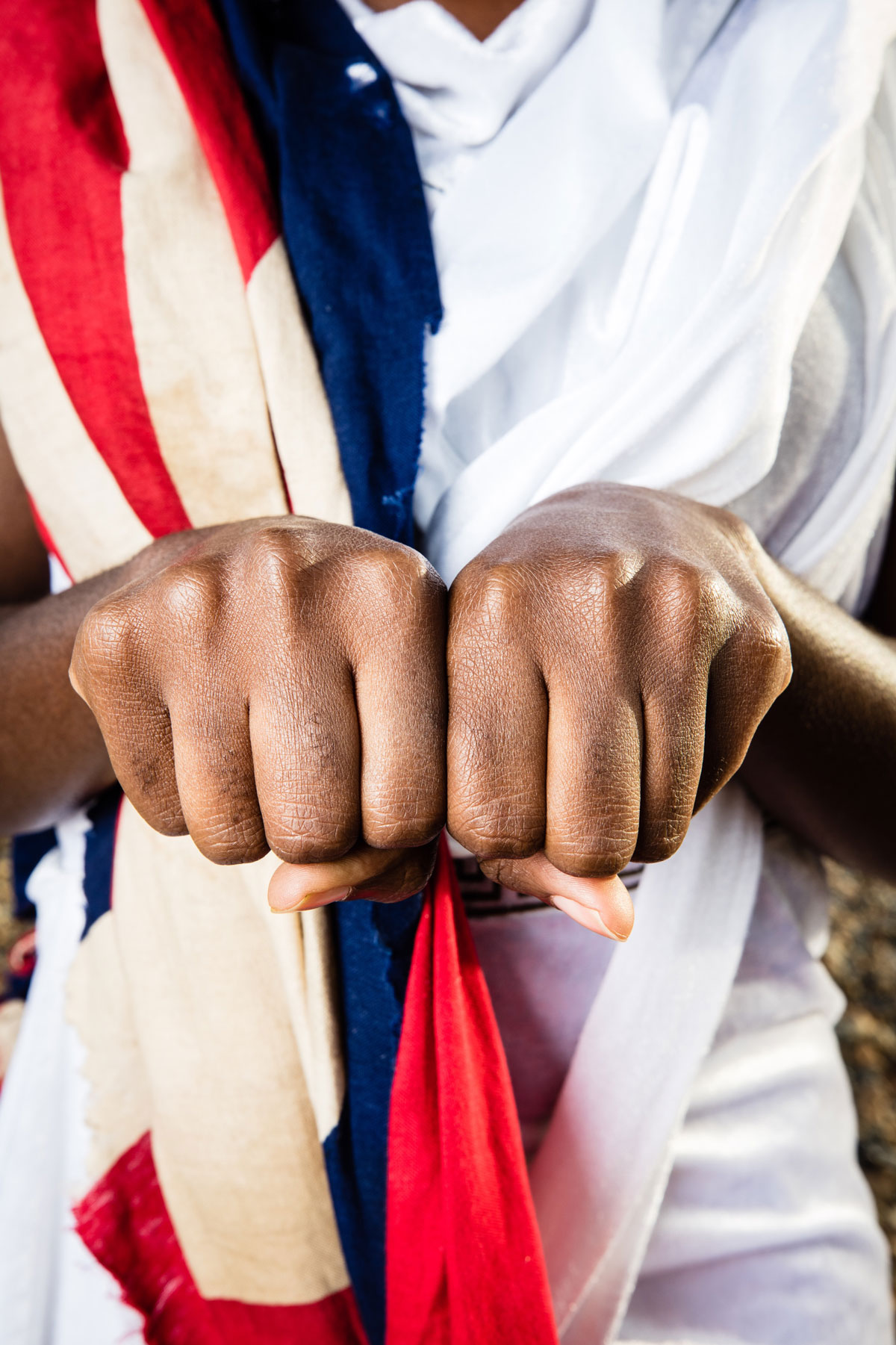

Heather Agyepong

How will Britain change?

What do you want post-Brexit Britain to look like?

How will it change your family?

How will it change your day-to-day life?

What will you read in the newspapers?

What will political conversations be like?

How will it impact your life positively?

How do you want people’s attitudes to change?

Do you want people to realize certain things? If so, what are they?

What do you want for the people who you feel have been left behind?

How do you want it to change for marginalized communities?

What will Britain’s new values be?

Habitus: Potential Realities was a community intervention project documenting the stories of young people, airing their concerns and hopes for British identity after we exit the EU. In partnership with Photoworks and Brighton & Hove Libraries, the project set out to re-imagine our idea of what it means to be British, turning current anxieties and fears concerning Brexit into a cathartic and optimistic outlook for the future of the young. Through an open call, participants were challenged to imagine potential new realities, using creative tools and cultural engagement to re-examine their perspectives.

An estimated 75% of young people voted remain in the EU referendum. Studies indicate a strong sense of anxiety within this demographic as they look towards the future. Recent LSE research reports widespread fears and concern about rising inequality, racism, intolerance, and declining multiculturalism.

As a British-Ghanaian artist who suffers from mental health issues, I am keen to address some of these anxieties. I have found that a useful exercise in addressing an anxious, voiceless or unheard sense of self is to develop a creative platform through which to re-imagine possible healthy, constructive outcomes, promoting a positive sense of empowerment, confronting the face of political chaos.

Despite their fears, the majority of young people in the LSE study were adamant that they want post-Brexit Britain to be a better place than it is now. Through this participatory photography project I unpack and challenge participants’ current perspectives, and share the perspectives of marginalized communities, especially those that often feel displaced by default, struggling to identify where home truly is.

Britannia, the female personification of Britain, warrior and caretaker of the sea, embodies the perspectives, values and ideals of the new Britain that the young people would like to see.

d

clustered | unclusteredAt Saturation Point: Brexit, New Labour and the Bleaching of English History in Martin Parr’s Documentary Think of England (1999)

Holly Brown

More than any other living artist, Martin Parr has dedicated his life and practice to a consideration of what it means to be English. His camera has always been directed at the eccentricities of English culture not normally favoured by the art world. Speaking of Parr’s cultural significance, Grayson Perry commented: “We see a queue of posh people, a buffet served on a Union Jack tablecloth or a lurid beach scene and we think of his work. He is one of the foremost chroniclers of our times.”1 And so, Parr’s prolific and anthropological oeuvre seems like an appropriate place to look when searching for an answer to the question of exactly how we came to be here: a parliamentary system and a country in stasis, paralysed by the question, “Who are we?”

It is this very question that forms the basis of Parr’s documentary Think of England, which was filmed in the summer of 1998. Parr travels the country, and shielded behind his camera asks his subjects: “What does it mean to be English?” The documentary portrays a country in flux, taking its first breaths after eighteen years of Conservative Party rule. We are told by a cheerful Glastonbury goer that he would “like to see the happiness of that bright May day” in 1997 when Tony Blair was elected continue. But while this optimism, which characterised English political life, has surely ebbed away, what remains consistent between our current moment and then is the insidious racist, xenophobic nationalism that runs through English culture. In the highly saturated images that characterise Parr’s work, we witness the ways in which English history has been whitened, its imperial past deliberately occluded.

Patriotism imbue the film’s subjects. One man laments that Rolls Royce has been absorbed by BMW and therefore has come under German control. A couple eating a roast dinner by the seaside say that they can’t imagine holidaying anywhere else. As historian Paul Gilroy has argued in the 2003 introduction to the now classic There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack, a sense of national pride was central to New Labour’s popularity. The success of British pop acts such as Blur, Oasis and the Spice Girls, and the worldwide popularity of fashion designer Alexander McQueen had led to a sense of national optimism that was encapsulated by the phrase “Cool Britannia”. As the Union Jack adorned Geri Halliwell’s dress, the flag’s association with colonial and imperial history became distorted.

Gilroy helps us see the significance of this in the long term. In adopting the symbols of nationalism without interrogating their histories, New Labour enacted a blank refusal to engage with England’s colonial past, a move that fundamentally altered the character of national discourse. New Labour essentially uncoupled the question of racism from debates over immigration. Instead of speaking in overtly racist terms, Labour’s leaders used an “alternative phraseology in which it is not racialised immigrants but non-racial refugees and asylum seekers who must bear the brunt of xenophobia and hatred.”2 From the continual erosion of the rights to asylum seekers which was legislated at the beginning of the twentieth century, to Gordon Brown calling for “British jobs for British workers” in 2009, New Labour’s policies and rhetoric made the statements of ultra-nationalist groups such as the British National Party and, more recently, the UK Independence Party seem respectable.3

New Labour succeeded in seeming “tough” on immigration, important in the handful of constituencies where the outcome of British general elections is settled.4 But their unabashed adoption of England’s national symbols, embedded in brutal and violent histories of colonial exploitation, allowed for the normalisation of a rhetoric arguing that England is an island nation that should be proud of its past and defensive of its borders.

It is also important to remember here that, though the coverage of Brexit referendum and its aftermath would have one believe differently, this idea was created and nurtured by Britain’s political class and elite, not by the politically disenfranchised and downtrodden. Perhaps the ghastly culmination of this process can be seen in Nigel Farage’s poster that was unveiled before the referendum. Farage chose not to show us, as public intellectual Akala rightly reminds us, “a bunch of French or Germans hopping across the channel at whim [...] He chose to show a face of dusty poverty that would apparently sneak into Britain via the EU.”5 It is perhaps not that EU nationals living in the UK are experiencing something new. The “hostile environment”, nurtured by Theresa May both in her time as home secretary and subsequently as Prime Minister, has merely been extended to EU nationals.

What is fascinating about Parr’s film is that we see how the accepted rituals of Englishness – tea parties, country fetes, the horse races – so quickly slip into assertions of superiority. When asked about their Englishness, the subjects of Parr’s film don’t hesitate to make bold claims. “Why would we need anything else when we have it all here?” and “It’s the best place in the world” are readily offered up, almost as verbal tics.

One wonders if these would have been presented so readily had Parr given a more accurate picture of multicultural Britain rather than the almost exclusively white subjects he seeks out. Think of England thus acts as a powerful cultural artefact that connects New Labour’s deliberate historical amnesia and the political disruption of the referendum. With the date of Britain leaving the European Union ever-delayed yet still looming, perhaps what is important to ask at this particular moment is for honesty not only about England’s, but also more widely Europe’s violent colonial past and present.

Notes

- 1Grayson Perry, “Martin Parr: Made in Britain”, The Guardian, 24 February 2019

- 2Paul Gilroy, There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack: The Cultural Politics of Race and Nation (London: Routledge, 2003), xxxv.

- 3For a detailed overview of New Labour’s restrictions on asylum see Will Somerville, “The Immigration Legacy of Tony Blair”, Migration Policy Institute, May 10 2007

- 4Gilroy, xxxv.

- 5Akala, “The battle of Britishness in the age of Brexit: Akala talks to the Convention”, 31 May 2017