115 — January 2026

Key Quotes and episode descriptions selected from series 3 episodes 9–12 of ‘Who Shat On The Floor Of My Wedding’ a.k.a ‘Rural Rectal Rampage’:

Part 1 (series 3, episode 9)

The quiet streets of Chipping Norton are no longer at peace. A phantom prankster - or perhaps an organised ring of pranksters - is targeting local stores and tagging innocent household items with stickers that say “for rectal use only.”

As the town’s elderly residents grow increasingly distraught, the pressure mounts on Detective LK and KW to put an end to the chaos.

Assistant to the Detective Karen Whitehouse: This is where I live, I have to go into this supermarket and this shop, on a weekly basis, so I’m not sure I even wanna digitally flash phallic objects.

Detective Lauren Kilby: No I get it, it’s your place, you live here, whatever, bla bla bla, reputation, I don’t care.

Assistant to the Detective Karen Whitehouse: If I came into your office of work and I went to your boss and I digitally flashed this at your boss…

Detective Lauren Kilby: Stop saying digitally flash.

.................

Shopkeeper: I was quite shocked frankly. It was quite weird, but not appropriate for a store with families. So we quickly went round and removed them all.

Detective Lauren Kilby: So you were concerned about the children.

Shopkeeper: Yes. And the elderly. They wouldn’t understand it, they would think that we’d probably put them on there, and obviously we didn’t want that reputation.

.................

Detective Lauren Kilby: Every time you see a penis, you imagine a sticker on it?

Shopkeeper: Yes.

Detective Lauren Kilby: I just want you to be able to make love to your partner and not worry about stickers.

Shopkeeper: I…

Detective Lauren Kilby: Did I cross a line? She’s leaving, she’s walked out.

.................

Assistant to the Detective Karen Whitehouse: If I could get your number, and we can be WhatsApp buddies, cause I feel like right now we’ve already crossed the boundary of friends… I was gonna say you should probably send me an aubergine emoji…

Detective Lauren Kilby: But that’s fucked.

Undercover teenagent: Fucking weird, I’m 19.

Assistant to the Detective Karen Whitehouse: Oh yeah, ok, definitely don’t do that.

.................

Detective Lauren Kilby: God, it’s really questionable what we do.

Part 2 (series 3, episode 10)

The investigation reaches new levels of desperation.

We find ourselves loitering outside a school, attempting to brief two teenagers on an undercover mission. We consult a nurse about the medical implications of anal insertions. And out of nowhere, a mysterious stranger appears with divine intervention.

But nothing prepares us for the final question… is this scandal confined to Chipping Norton... or is it far bigger than we ever imagined?

Assistant to the Detective Karen Whitehouse: We are not going undercover at a teenage party.

Detective Lauren Kilby: Why?

Assistant to the Detective Karen Whitehouse: Ok, let’s do a little roleplay. Who are you?

Detective Lauren Kilby: Hey, I’m friends with, um, your mum.

Assistant to the Detective Karen Whitehouse: Ok cool, and then what do you do?

Detective Lauren Kilby: And then I’ll go ‘Hi everyone, quick announcement, does anyone recognise this sticker’ and that’s all, and I’d be miked up. It’s not that big of a deal, it really isn’t.

Assistant to the Detective Karen Whitehouse: It could be a very big deal, I think, if a random woman gatecrashed a teenager’s party showing them a rectal stickers picture - and there will be other parents there I imagine.

Detective Lauren Kilby: It could also be not a big deal, and just fine.

Assistant to the Detective Karen Whitehouse: Yeah no, it might not be a big deal, but the chance of it being a big deal is definitely an option there. The chance of someone calling the police is actually a quite, um, reasonable course of action.

.................

Assistant to the Detective Karen Whitehouse: I think the headteacher will be like ‘get that down now, who told you to put that up’ and then we’re gonna get sent to the fucking principal’s office. I live here, we’re not doing that.

.................

Detective Lauren Kilby: Shall we go into the school?

Assistant to the Detective Karen Whitehouse: Can you imagine how that would go, have you got a visitor’s pass, no, which one of the children is your child, none of them, we are childless detectives.

Detective Lauren Kilby: Childless fake detectives.

Part 3 (series 3, episode 11)

A prime suspect suddenly blocks Karen from all forms of communication, disappearing without a trace. Meanwhile, a reckless pyramid scheme involving teenagers spirals wildly out of control, taking the case to fresh levels of unprofessionalism.

Desperate for answers, Karen takes stalking to bold new heights, while Lauren conducts a final high pressure interrogation that could make or break the entire investigation.

Who truly set the Rural Rectal Rampage in motion, and what twisted mind wakes up one day and chooses this life?

Assistant to the Detective Karen Whitehouse: I think we’ve got a clear example here, Lauren, of where we’ve gone a little bit too far, is my gut feeling, from this conversation, and the pyramid scheme involving 11-year olds, I think we’ve hit… and it’s ok, to sort of hit the point where we’re like ‘this has gone too far’, I think we just need to reflect on that and take that away, take it offline and see…

Undercover teenagent: Ground yourselves.

.................

Assistant to the Detective Karen Whitehouse: Yesterday I went to meet a perpetrator and I came back with a friend.

Detective Lauren Kilby: Never say that again. You can’t use our podcast to increase your social network.

Part 4 (series 3, episode 12)

In the tense finale of ‘Rural Rectal Rampage’, we finally meet the shadowy figure pulling the strings behind the entire scandal.

What begins as a simple confrontation unravels into something far more complex... an unexpected motive that forces everyone to rethink everything they thought they knew about the crime... and about themselves.

As we piece together the true intent behind the Rampage, we arrive at a dangerous crossroads: is our duty simply to solve crimes… or has this investigation pushed us toward actually committing one?

Mr Inappropriate: It all came from observing people in the workplace, seeing them struggle, and also knowing a lot of friends and people I work with struggling with confidence, and feeling like they’re not allowed to be themselves, a feeling of not being able to just be who they want to be. And I think just giving people permission, you know, if you give someone permission to do something, then it’s ok. So if you give someone permission to do something very very naughty, then it kind of releases them to do whatever they want to do in other ways as well. You know I find certainly that misbehaving, in whatever way it is, doesn’t matter, misbehaving is a good release, it’s like taking the lid off a pressure cooker, it’s just good for you. Right? And that’s what it’s about.

Detective Lauren Kilby: I like that you’re in charge of giving permission, globally, to be inappropriate.

.................

Mr Inappropriate: It’s just an escape that I think we all need. Same with you guys, you know, I think what you do is great, we’re all just sort of conditioned to live in a certain way and people don’t question it. You spend a lot of time lying down and then you go to work and then you spend time doing stuff you don’t like with people you don’t like, doing something you don’t care about, and then you go back home and sleep and you keep doing that until you’re dead, it just sounds very silly, and a moment of escape from that is really healthy, I think.

.................

Mr Inappropriate: Sticking a ‘rectal use’ sticker on something is for many people just a first step of releasing yourself from the social restriction that we’re all bound by. So I think it needs to be first in a sequence of things.

.................

Assistant to the Detective Karen Whitehouse: What message would you like to share with all of the perpetrators of this prank?

Mr Inappropriate: My message is for you people to be creative and proud. If you think ‘oh no, I can’t stick it there because that’s terrible’, that means that’s where you need to stick it. And if you think you might get caught and terrible things might happen, that’s where it needs to go.

Assistant to the Detective Karen Whitehouse: What message would you like to share with the people that haven’t yet had the confidence to use the stickers you’ve sent them?

Mr Inappropriate: These stickers are for you. If it’s easy for you to stick the stickers somewhere you shouldn’t, then, that’s fine, brilliant, do it, it’s funny. But the real benefit is for those of you who find it difficult. This is a first step to learning who you really are and being yourself.

.................

Detective Lauren Kilby: What does this mean for your reputation? I think this is a good thing?

Assistant to the Detective Karen Whitehouse: I dunno, I mean I walked around the local supermarket the other day and I saw Megan and they’re all a bit scared of me in there.

Just Safe Enough For Work.

Beating the bounds of the appropriate in ‘Who Shat On The Floor At My Wedding’, the Performance Art workplace, and a Group Relations Conference

Francesca Hawker

1.

‘Who Shat On The Floor At My Wedding’ (WSOTFAMW) is a faux-true-crime podcast, distributed by Acast from 2020 to 2025 and created and hosted by ‘Detective’ Lauren Kilby, ‘Assistant to the Detective’ Karen Whitehouse and ‘Assistant to the Assistant to the Detective’ Helen MacLaughlin. Karen and Helen decided to start an investigation on hearing that, as the title indicates, someone had ‘shat on the floor’ of the boat in Amsterdam where they had held their wedding. They hired their friend Lauren as an ‘unqualified detective’ and formed a crime-fighting trio in order to attempt to crack the case. Following popular success (regardless of whether or not they actually managed to find the culprit) they have gone on to tackle a number of other people’s ‘non-crime crimes’ across three series, including that of Lauren’s mother-in-law who found a small corduroy suit on her porch in Sweden (a case of ‘reverse theft’), and that of a listener whose house was broken into and thoroughly cleaned (a case of reverse vandalism).

Did I cross a line?

Their investigative method involves sourcing collaborators from their network of family, friends, and friends of friends, in order to interrogate them as witnesses or seek their advice. Some of them need a push to overcome their doubts, suspicions or disinterest in order to participate, often in the form of overly fawning emails that are narrated to us as listeners. Professionals, such as a forensic psychologist, are also enlisted. They too have concerns but of a different form: they worry about whether participating could harm their careers. But in all cases the hosts relentlessly persevere, like stand-up comedians goading a nervous audience into crowdwork. It wouldn’t be funny for the listener or enticing for the guest if the atmosphere was safe and benign. But to establish just enough real risk, the scaffolding must first be constructed, consisting of a set of assumptions that can explain the worries away, diverging along different lines depending on how closely they all know each other. The close acquaintances or friends of friends can reasonably assume that the hosts depend on the relationship surviving beyond the podcast, or at least on any issues that arise being reparable through the bonds of a shared social network. And an expert, for example the forensic psychologist, might fall back on the absurdity of the podcast, on its distance from their actual profession. It might even become something to laughingly include on their CV.

Series 3 of WSOTFAMW diverges from series 1 and 2 in a couple of ways. For one, Helen (the Assistant to the Assistant to the Detective and Karen’s wife) has been amicably fired. More importantly, series 1 and 2 each focussed on one non-crime crime each, but in series 3, a new non-crime crime is introduced every few episodes. Therefore, episodes 9 to 12 of series 3 form a four-part mini-series with its own title: ‘Rural Rectal Rampage’. This mini-series takes place in a new kind of context, inhabited by a new kind of participant. The mini-series is birthed by Karen’s love for the community Facebook page of Chipping Norton, the small village in the Cotswolds where she lives. While scrolling, Karen notices a picture of a phallic vegetable with a small sticker on it that reads ‘for rectal use only’. She and Lauren open an investigation into what turns out to be a non-crime wave: hundreds of items in countless stores have been affected, and villagers have no idea who the perpetrators are. The mini-series is thus presented as creating a new capacity for risk on the side of the hosts due to Karen’s reputation as a villager being on the line, depending on the outcome of their investigation. And with this new consideration comes the golden comedic opportunity to maximise the anxieties that come with it.

It’s not that the hosts have never worried about their own reputations before: they often express incredulity at the fact that this (producing a podcast about non-crime crimes) is their profession (more on this bemused stance later). However, for the first time (or what’s presented as the first time) one of the hosts has a particular kind of social skin in the game. It is not her reputation among friends or strangers that is at stake, but among neighbours who she sort of knows. Within this dynamic, Karen’s odd behaviour can’t necessarily be explained away in terms of knowledge of her personality (‘that’s just Karen’) or her relative harmlessness due to lack of proximity (‘I’ll never need to speak to this woman again’). The digital and global space of the podcast begins to intersect with the local, quotidian space of rural England, where groceries need to be bought and parcels need to be collected. The fact that whatever happens in the podcast, Karen will need to continue interacting with (and potentially relying on) these acquaintances charges the mini-series with potentially destructive ramifications, in which neighbourly relationships (that lack both the inherent quality of reparability afforded to friendship and family, and the relative safety of anonymity) risk being irrevocably damaged.

I live here, we’re not doing that.

Without a follow-up episode to fully gauge whether Karen did or didn’t become the village pariah, we can’t say for certain whether this was ever on the cards. Nevertheless, they frame the show as a bid for Karen’s reputation, through constant reminders during introductory statements and behind-the-scenes chatter.

No I get it, it’s your place, you live here, whatever, bla bla bla, reputation, I don’t care.

The excitement the listener feels at the thought of things going slightly too far during an interrogation or a lie-detector test is what makes the series as a whole so successful, in particular thanks to Detective Lauren’s threatening deadpan demeanour sweetened by her winning New Zealand accent. Inevitably, as is the case throughout the podcast, the guests who choose to take part in ‘Rural Rectal Rampage’ are self-selecting. Although often hesitant at first, perhaps their reluctant stance enables them to explain away their participation to their loved ones. The same logic of reluctance-as-exoneration again applies to the stand-up context, in the example of someone sitting in a front row seat at a comedy club and burying their face in their hands as they’re picked on. Moreover, isn’t it more likely that Karen will come away from the experience having endeared herself to the village as a wacky but ultimately lovable ‘character’, the kind a village enjoys having in its roster of inhabitants? And if not, doesn’t the gamble for the listener’s glee at this supposed risk-taking behaviour not ultimately outweigh any social risk that Karen may experience, which at most might amount to a glare in the supermarket?

Yesterday I went to meet a perpetrator and I came back with a friend.

Never say that again. You can’t use our podcast to increase your social network.

This reading of Karen’s reputation in the village as ultimately safe is complicated by two factors: Firstly, in the one context where ‘actual’ reputational damage is purportedly at stake, Karen and Lauren choose to trespass further beyond the bounds of the inappropriate, and even into the territory of the potentially illegal. This manoeuvre therefore chips away at our confidence in the harmlessness of their actions. We see this most clearly in their hiring of undercover ‘teenagents’, which involves hanging around outside a school in order to solicit secret meetings in their car. Why does this particular context, in which there are performatively heightened yet tangible risks, lead them to be even more reckless with their reputations?

As stated earlier, the extent to which they are actually entering dangerous territory is hidden from the listener for comic effect: we never learn, for example, whether or not the school actually had prior knowledge of these meetings. And we get the sense that this atmosphere of ominous ambiguity also exists on the ground, as one of the undercover ‘teenagents’ tells them that his mum received a text from another mum asking why he was going around school talking about rectal stickers. In this way, they could genuinely appear to the village to be acting nefariously, which is exacerbated by a second, inter-related complication: the village context (in which gossip is rife) causes the fieldwork undertaken by Lauren and Karen and the narrative it precipitates to leak out of the production studio and beyond their control, into the lawless streets of Chipping Norton. For the listeners of the podcast, our previous knowledge of the harmlessness of the hosts allows us to bracket these behaviours as benign. But isn’t the corruption of children something no amount of ‘it’s for a podcast’ can explain away in the face of a concerned parent?

I think we’ve got a clear example here, Lauren, of where we’ve gone a little bit too far, is my gut feeling, from this conversation, and the pyramid scheme involving 11-year olds, I think we’ve hit… and its ok, to sort of hit the point where we’re like ‘this has gone too far’, I think we just need to reflect on that and take that away, take it offline and see…

WSOTFAMW is shaped through its central inappropriate gesture of treating a non-crime crime as a crime, and the subsequent absurdity of all of the behaviours that follow this illogical logic: masquerading as detectives, pressuring friends and family into the roles of suspicious criminals instead of beloved wedding guests, and wasting the precious time of forensic professionals. But Lauren and Karen’s inappropriateness mostly avoids risking real social consequences thanks in part to their comedic framing, and the nature of their relationship to their chosen collaborators, socially and geographically speaking. In ‘Rural Rectal Rampage’, they shift gears and attempt to work on home turf, amongst people who are part of Karen’s everyday life and for whom she needs to maintain an acceptable reputation in order to keep her life running smoothly. This change in the stakes and relative risk posed to the hosts tellingly coincides with a change in their behaviour and in their working environment: a lack of control over the narrative and a murkiness between what’s real, what’s pretend, and who’s supposed to be who, as they morph from faux-detectives to potentially real criminals.

2.

In order to think further about the landscape of propriety, risk, and social visibility being navigated in this mini-series, I’ve been cross-hatching it with a scenario I encountered at the Tavistock Centre in London, where I took part in a week-long ‘Group Relations Conference’ (please visit https://www.nplusonemag.com/issue-51/essays/experiences-in-groups/ for an excellent and more in-depth account of the experience of experiencing Group Relations, especially as a relative ‘outsider’). The conference consisted of five 8-hour days in which groups of people gathered to experience what it is to be a group, and therefore to collectively produce knowledge about groups. There were big groups, small groups, randomised groups, chosen groups, and groups in which there was conflict, boredom, laughter, silence. The groups shifted in size and number throughout the day, meaning each member had a range of experiences to compare and contrast.

This model of Group Relations stems from the work of English psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion, later developed into conference formats at the Tavistock Clinic in the 1950s and 60s. Bion’s biggest innovation (as far as I can tell) is the idea that one should see a group as an entity of its own with its own unconscious assumptions, which are inevitably channelled through individuals in the group at any given moment. According to Bion, a participant might take on a ‘role’, for example that of a leader, and the group might then respond in a number of semi-predictable ways. The way in which the group is acting or feeling is commented on by ‘consultants’ throughout the conference, similar to how a psychoanalyst might offer their observations to a patient, who could then choose to explore or reject these hypotheses.

In the context of the conference, I was very much an outsider in multiple respects. I was relatively ignorant about the methodology of Group Relations, and I wasn’t in training to become some kind of psychoanalyst, psychologist, or social worker, which in this particular conference (though this isn’t always the case) put me in a tiny minority. And maybe most importantly, I was presenting myself - and being presented as - ‘an artist’. By the end of the week I had been thoroughly reminded of the privileges afforded to you when you go around saying ‘I’m an artist’ in a room full of non-artists, probably similar to what happens if you go around saying ‘it’s for a podcast’. I was equally quick to tell everyone ‘it’s my first time!’ This process of deference, as a guard against expectations, felt familiar, as it’s also something I do in my performance art practice, often at the beginning of a performance. I say (or insinuate) that ‘I don’t know what’s going on’, which can create a confusion about my role as the ‘leader’, despite me still holding the microphone.

As well as knowing nothing about Group Relations, I (almost) didn’t know anyone. I didn’t know the ‘consultants’, I didn’t know Wilfred Bion. The only person at the conference I’d met before I’d met only once, but despite our tenuous connection, our conversations quickly developed what felt to me to be a conspiratorial air. I therefore felt indestructible, free to do whatever I wanted with no social restrictions, fuelled by the presence of an ‘accomplice’. In other words, the social landscape was ostensibly inverted in comparison to that of Lauren and Karen in ‘Rural Rectal Rampage’: they were working in the murky middle, with no friends and no strangers, only acquaintances.

At the peak of my confidence roughly halfway through the conference, I was sitting in the second row of a three-row spiral of around 60 chairs. I found myself passionately exposing to the group the fact that we had almost entirely avoided talking about sex and attraction. My reasoning, as I explained, was that this area of discussion, usually inappropriate in a room full of strangers, was surely nothing if not entirely appropriate in this particular context. A bronze statue of Freud was sitting outside the building, and as I sulkily pointed out, the room was filled with budding analysts. Wasn’t this their job? Wasn’t this the point? I didn’t actually share anything, I just pointed out that nothing of this sort was being shared. But following my invitation, many people then went on to share erotic thoughts and associations, some of which I found entirely inappropriate.

The next day, sitting in the same 60-person spiral format, a member told the group that the conversation that had stemmed from my proposal had caused them harm, and had therefore trespassed out of the bounds of appropriateness and into the realm of the prohibited. They explained that this was a workplace, which therefore required adequate safeguarding. Like the podcast, the scenario had gone beyond the merely cheeky to infringe into territory that chimed with forms of illegality (workplace sexual misconduct, to name the most glaring) but unlike the podcast, the situation was decidedly unfunny.

And then I’ll go ‘Hi everyone, quick announcement, does anyone recognise this sticker’ and that’s all, and I’d be miked up. It’s not that big of a deal, it really isn’t.

The member who designated the boundary had felt infringed upon by the content of the conversation, and there was no escaping the reality and significance of their testimony. But integrated within this moment there seemed to exist a fundamental and intriguing disagreement regarding the nature of the situation we were in: was this a workplace, and if so whose? And if it is a workplace, who let me in and why? Shouldn’t I have been denied entry? The lack of a clear authority figure present to make a decision like this one was a key anxiety felt throughout the conference: the ‘consultants’ appeared authoritative, but despite acting unusually, didn’t make decisions on behalf of the group. Without an obvious leader, the situation failed to read as ‘professional’ or ‘educational’ in any recognisable sense. How then to define a situation as appropriate or not, if propriety is context-specific and the context itself is under question.

In some contexts (including workplaces) the presence of ‘an artist’ can cause a rupture. It might be significant and longlasting, or it might allow for a necessary release in order to give voice to the Not Safe For Work (NSFW) before a return to productivity. I imagine that my awareness of these kinds of scenarios emboldened me to take on the role of an artist in a non-art context. This role relies on the assumption that, in contrast to the employees, you have ‘nothing to lose’, which in turn relies on being in a game-like scenario with no exterior consequences. But as the week had gone on, the context had somehow morphed into that of a village rife with allegiances and gossip, mirroring the way the context of ‘Rural Rectal Rampage’ blurred into an unpredictable social landscape. What did this mean for my behaviour; its origins, reception, and afterlife?

I think the headteacher will be like ‘get that down now, who told you to put that up’ and then we’re gonna get sent to the fucking principle’s office.

Furthermore, this kind of disruptive role necessitates a presumption of ignorance, either in the eyes of others or in one’s own estimation. It’s somehow assumed that someone stumbles into inappropriate territory because they didn’t know the rules. But isn’t it actually the case that the presence of the inappropriate, as opposed to the prohibited or harmful (which stops or ‘cancels’ action in its tracks), demonstrates a certain saviness in regards to propriety? The inappropriate subject must surely have been equipped with a road-map in order to avoid prohibited areas in favour of inappropriate ones. Successful inappropriateness can therefore endear the audience and create a space for complicitous engagement in the knowledge that they’re in safe and knowledgeable hands. In the case of the scenario described above, we fell out of the realm of the inappropriate and into the prohibited, but I was left wondering if the subject matter itself was truly out of bounds, if indeed I hadn’t ‘known the rules’ or whether, through comedic, tactful, or organisational alterations, things could have gone differently.

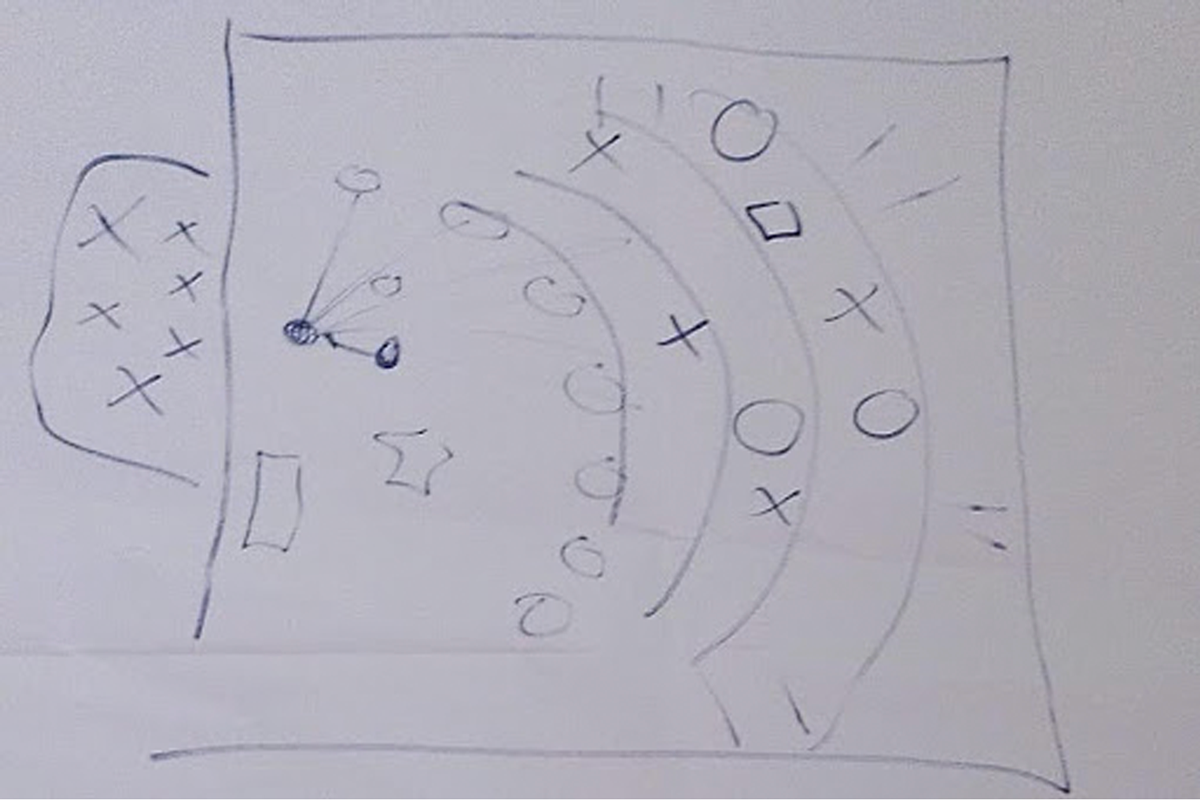

In the final small-group session, I was invited to reflect on how I might take the week’s experiences and integrate them into my own professional context. I explained to the assembled audience (a group of mostly psychologists-in-training) that I live and work within a social scene in which artists and curators, friends and strangers, attend each others’ events. The roles are blurred: some people might be there ‘for work’ but also to socialise. I used the drawing in the image below to illustrate an example of an audience I performed to, populated with people I know (x’s) and people I don’t (o’s). The group sagely reflected that this seemed like a potentially paradoxical context in which to work. They noted that my behaviour in the conference thus far had been ‘jester-like’, and now they could also see that it is integral to my line of work to take social risks, both within a performance, and as fuel for future performances and for my PhD research on embarrassment. With this apparent need to embarrass myself and others, how do I draw up and maintain lines of propriety for a mixed audience of the people I know and the people I don’t, the x’s and o’s? For example, how can I argue that I ‘don’t know what’s going on’ if there are people in the audience who know that I actually do, thanks to our friendship outside of the space of the performance? And how does my need to stay within the (invisible) boundaries of propriety designated by a potential employer intersect with my need to explore this realm artistically?

3.

Lauren and Karen, the hosts of ‘Who Shat On The Floor At My Wedding’ (WSOTFAMW), frequently express incredulity at their own life path and surprise at the fact that somehow this has become part of their careers (in addition to their corporate roles in marketing and production). Their bemused attitude may stem from genuine confusion, but it’s also an expression of delight at having stumbled upon a way of life they couldn’t have predicted. I’ve noticed this observation being expressed fairly often among comics, and I hear myself saying it too: ‘I can’t believe I’m writing about a podcast with the word “shat” (the past simple form of “to shit”) in the title for an academic journal.’

God it’s really questionable what we do.

After the Group Relations Conference, I had a similar feeling: ‘I can’t believe I said that’. In our summary groups at the end of each day, where we would reflect on the strange behaviour we’d witnessed ourselves enacting, we would be reminded of Wilfred Bion’s philosophy of groups. Viewed through this lens, the confusion is somewhat justified, because ‘I’ didn’t really say what I’d said; or I did, but only because of a compulsion that had to do with the specific dynamics of the group I found myself in. In that case, what could we surmise the group was feeling? Why did the group want to talk about sex one day, and the next day want to stop talking about it?

Let’s return again to the idea that the labelling of something as inappropriate potentially signals a fundamental disagreement concerning the nature of the context in which the supposedly inappropriate thing occurred. Mirroring the way in which the analysts-in-training had observed the paradoxical nature of my workplace, in which differing bounds of propriety might eclipse each other, the scenario in the spiral of chairs had placed me in the role of an armchair analyst, observing the way in which a provocative and exploratory drive might threaten a competing drive towards maintaining professional boundaries. Presumably, the nature of a medicalised workplace such as this, invested in projecting an air of regulation (in contrast to the performatively laissez-faire attitude of the art world), magnifies this paradox. Perhaps, then, the rapid uptake and equally rapid rejection of this discourse was a convenient way for the group to highlight a disciplinary norm in the face of an impossible situation, without doing damage to the reputation of someone who was known within the context, and who professionally ‘mattered’.

Or, is it just that some members of the group wanted one thing and others wanted another, and therefore this culminated in a ‘yes’ to a question, followed by a ‘no’? Is the group really so unified or is the idea of ‘the group’ a representation of certain individuals within it? If so, which individuals: whose needs are the group interested in meeting? Which needs ‘won out’ in the scenario described above? I found myself wondering if it had something to do with my apparent difference within the group, as an artist but also as a queered subject, that beckoned the erotic into the room. Despite establishing that I use she/her pronouns, there was a general sense of confusion and hesitancy around my gender identity, and I had the impression that among the relative heteronormativity of the conference I was being read as a representative of the queer community. In this way, my anonymity could be read not just as an opportunity for me as an individual, providing me with the confidence I required to take on the role of conjuring the inappropriate, but also for the group, making it possible to project various assumptions which in turn created a set of behaviours. From another angle, we could consider the group as having attempted to exorcise the potentially destabilising (and therefore frightening) element of sexuality from within its makeup by inviting and then rejecting it through the equally frightening element of queerness, and in doing so marrying one danger to another in an act of equation. By identifying the omnipresence of sexuality (a societal given) with a projection of queerness (a state of being perceived to be outside of the norms) the expression of sexuality could theoretically be placed outside of the bounds of the normal in a sleight of hand.

I was quite shocked frankly. It was quite weird, but not appropriate for a store with families. So we quickly went round and removed them all.

In ‘Rural Rectal Rampage’, despite the constant hand-wringing about Karen’s reputation, it’s clear that many villagers are eager to play in this space of impropriety, most notably the non-crime criminals that stuck the stickers in the first place and prompted the investigation. Therefore one reading of Karen and Lauren’s apparent extravagance in leaning into ever more absurd behaviours is that they were answering a call from below the surface of the village for some kind of watershed moment, some kind of reckoning with the erotic. And yet, perhaps the severity of Karen’s fears of being socially marooned, and even the drive towards making this more likely, also stem from the same local unconscious, and from collectively and culturally held assumptions around what usually happens in the context of a village like Chipping Norton, historically a Conservative stronghold, when two women cosplaying as detectives investigate an influx of stickers referencing queered sex acts attacking innocent supermarkets.

Ok, let’s do a little roleplay. Who are you?

Hey, I’m friends with, um, your mum.

By thinking about groups in this way, as both the individuals contained within them and simultaneously as something more than the sum of their parts, we get closer to how it feels to be in the group of a performance, consisting of the performer(s) and audience members. As in all groups, feelings can originate in one person and end up in another. And as LARPers (Live Action Role Players) will tell you, it’s often the case that a ‘bleed’ will occur (akin to ‘transference’ in psychoanalysis): a moment in which it won’t be clear where the performance ends and ‘real’ life begins. This phenomenon is informed by and acts on the relationships in the room, leading to a confusion around how to understand what’s happening and which conclusions to draw from it. As Lauren and Helen discover in ‘Rural Rectal Rampage’, the group of neighbours, when re-cast as a group of collaborators, still retains traces of its neighbourly-ness, leading to a heady atmosphere which precipitates (and is held together by) a comedic logic, yet which risks prioritising its own needs for village peace. And in the Group Relations Conference, my initial lack of reckoning with my own implication in the fabric of the group and the ways in which the group might ‘work on’ me, and I on it, lead to unforeseen threats to my intention to limit my role as a jester (and the subsequent consequences of my provocative actions) to the realm of a game.

4.

In the final episode of ‘Rural Rectal Rampage’, a new guest is introduced: Mr Inappropriate (aka Dave), an IT worker who also runs a successful business selling novelty items plastered with NSFW slogans and cartoons. It was he, they discover, who has been including complementary ‘for rectal use only’ stickers in all the purchases he ships, making him the ‘global mastermind’ of the trend.

So if you give someone permission to do something very very naughty then it kind of releases them to do whatever they want to do in other ways as well.

I like that you’re in charge of giving permission, globally, to be inappropriate.

If social exclusion is avoided, what is the potential reward that Mr Inappropriate is insinuating his customers will receive following a successfully inappropriate moment, a.k.a. secretly placing a sexually suggestive sticker onto a supermarket item? His closing statements at the end of the episode, in defence of inappropriateness as though it’s been put on trial, imply that one small act like this marks the beginning of a journey of discovery, which awakens people to the mundanity of modern life.

You spend a lot of time lying down and then you go to work and then you spend time doing stuff you don’t like with people you don’t like, doing something you don’t care about, and then you go back home and sleep and you keep doing that until you’re dead, it just sounds very silly, and a moment of escape from that is really healthy, I think.

However, as he says himself, the things he sells are tools with which to ‘escape’ the 9-5. Mr Inappropriate is not a full-time job but a role Dave sometimes plays, and a role I see myself as attempting to inhabit whenever I try to maintain a healthy work-life balance in my performance practice. He seems content to be ‘Mr Inappropriate’ on the weekends in order to provide himself with a supplementary income, in the same way that I have an economic interest in being appropriately subversive. And his customers, through his inappropriate tools, receive a carnivalesque relief from the bonds of capitalism.

What message would you like to share with the people that haven’t yet had the confidence to use the stickers you’ve sent them?

These stickers are for you. If it’s easy for you to stick the stickers somewhere you shouldn’t, then, that’s fine, brilliant, do it, it’s funny. But the real benefit is for those of you who find it difficult. This is a first step to learning who you really are and being yourself.

To return once more to Lauren and Karen, we can perhaps assess ‘Rural Rectal Rampage’ as such: an example of what happens when you allow your art to converge with the place you would otherwise try to escape, a place in which the civil requirements of the everyday create an obscure terrain, studded with social pitfalls as well as comedic possibilities. Although they exceed their expectations and catch not only the local but global perpetrator of the non-crime crime, thereby achieving the goal that they thought would provide Karen with immunity and ‘local hero’ status, they end on an ambiguous note, thereby demonstrating how hard it is to assess the outcome of an individual project when it remains integrated within an amorphous group context:

What does this mean for your reputation? I think this is a good thing?

I dunno, I mean I walked around the local supermarket the other day and I saw Megan and they’re all a bit scared of me in there.

Thanks to Rikus, Marce, Anastasia, Arne and Margaux, for reading earlier drafts of this article.