114 — October 2025

Afscheid van het antropoceen

Lieven De Cauter

Het antropoceen is niet meer. De term is een stille dood gestorven. Dat is velen misschien ontgaan. Daarom lijkt het ons de moeite waard om een korte reconstructie te maken van dit technische debat over een term die weliswaar vanaf het begin controversieel was, maar tegelijk veelbelovend, omdat hij zo duidelijk en allesomvattend was: het geologische tijdperk van de mens, een tijdperk gedomineerd door de menselijke soort als geologische kracht die tot in de gesteentelagen zijn spoor nalaat en door die gigantische impact de ‘aardsystemen’ (Earth Systems) gevaarlijk uit evenwicht brengt.

Tegelijk dwingt het afwijzen van de term als geologisch tijdvak ons om op zoek te gaan naar andere termen die de krachten en gevaren van ons tijdperk voor de biosfeer, voor het leven op aarde, kunnen helpen benoemen. Ik sta hier stil bij twee termen: ten eerste het bij het grote publiek relatief onbekende begrip ‘the Great Acceleration’ of Grote Versnelling, dat juist werd gemunt in de zoektocht naar het begin van het antropoceen (de zogenaamde golden spike of gouden spijker); ten tweede de bekendere maar evenzeer erg recente terminologie van ‘Planetaire Grenzen’ (planetary boundaries). Het vertoog rond beide termen geeft heel goed aan hoezeer de wereld van de ‘Earth Systems sciences’, de meest brede benaming van alle wetenschappen die zich bezighouden met het leven op en van de planeet (dus breder nog dan alleen de ecologie van de biosfeer), haar hoop had gesteld op de krachtige nieuwe term antropoceen als nieuw geologisch tijdvak. Omdat die drie termen meestal gebruikt worden ‘van horen zeggen’, ga ik terug tot de bronteksten.

Korte geschiedenis van het antropoceen

In het symbolische jaar 2000 stelden Nobelprijswinnaar Paul J. Crutzen, een specialist in atmosferische chemie, en Eugene F. Stoermer, een ecoloog die gespecialiseerd is in onderzoek rond water, in een kort artikel in the Global Change Newsletter van het International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme, de term Antropoceen voor als nieuw geologisch tijdperk, om aan te geven dat de relatief stabiele periode van het holoceen achter ons lag en we een periode van instabiliteit waren binnengetreden onder invloed van de impact van de menselijke soort op het ecosysteem, vandaar de term antropo-ceen, letterlijk: het nieuwe tijdperk van de mens. Hun voorstel klonk zo:

Considering the [...] major and still growing impacts of human activities on earth and atmosphere, and at all, including global, scales, it seems to us more than appropriate to emphasize the central role of mankind in geology and ecology by proposing to use the term ‘anthropocene’ for the current geological epoch.1

Het gaat dus niet om de invloed van de menselijke soort op de planeet aarde, want die gaat duizenden jaren terug, maar het plotse veranderen van de totale toestand van de planeet door de invloed van de mens. Dat maakte de term vatbaar voor misverstanden. Want vanaf wanneer kantelt het? De industriële revolutie die Stoermer en Crutzen naar voren schoven als bijna vanzelfsprekend beginpunt, was misschien toch niet het moment dat de toestand van de planeet als geheel veranderde, en zo een einde maakte aan het holoceen.

.Een tweede mogelijke zwakte van hun voorstel bestond erin dat ze benadrukken dat het begrip tegelijk geologisch en ecologisch is. Dat klinkt holistisch maar is voor geologen misschien een reden om het begrip te verwerpen als te ecologisch. Voor Stoermer en Crutzen was het voorstel van een nieuw geologisch tijdvak in elk geval een tegelijk activistisch en wetenschappelijk programma:

To develop a world-wide accepted strategy leading to sustainability of ecosystems against human induced stresses will be one of the great future tasks of mankind, requiring intensive research efforts and wise application of the knowledge thus acquired in the noosphere, better known as knowledge or information society.

Uit het citaat en de hele tekst blijkt dat het antropoceen volgens hen een probleem is van de hele mensheid en dat er wordt gerekend op wetenschap en technologie om het op te lossen. Beide punten waren vanaf het begin voer voor discussie.

In elk geval kreeg het korte artikel een enorme weerklank. Zo werd in 2009 de Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) samengesteld, die het concept onderzocht en verder moest specifiëren. Pas eind 2023 had de AWG zijn onderzoek afgerond. In maart 2024 verwierp de International Subcommission on Quarternary Stratigraphy (SQS) het voorstel van het antropoceen als geologisch tijdvak met een verpletterende meerderheid van 12 tegenover 4 (met 3 onthoudingen). Deze beslissing werd bekrachtigd door de Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) en bezegeld door de hoogste instantie van de geologische wetenschappen, de International Union of Geologicial Sciences (IUGS). Nochtans was de Anthropocene Working Group vijftien jaar bezig geweest om de term te ijken, een beginpunt en een vindplaats te bepalen. Hoewel er andere data in omloop waren als ‘golden spike’, zoals de al genoemde industriële revolutie, de kolonisering (de zogenaamde Orbis Spike),2 en zelfs de landbouwrevolutie van 10.000 jaar geleden, won het voorstel om het antropoceen te laten beginnen rond het midden van de 20ste eeuw. De atoomtesten en ermee samenhangende geologische resten plutonium werden als gouden spijker genomen; de datum was 1952 en de vindplaats werd bepaald op Lake Crawford in Canada. Een belangrijk argument voor die wat vreemde keuze voor een zo recente datum, en niet voor de vanzelfsprekende datum van de industriële revolutie, was de zogenaamde ‘Grote Versnelling’, de exponentiële toename van socio-economische parameters zoals bevolking en economische groei en de impact ervan op het ecosysteem. Wellicht heeft echter de keuze voor een zo recente datum de doorslag gegeven om de term antropoceen te verwerpen, want de impact van de mens op de planeet dateert uiteraard niet van gisteren. In de verklaring van de International Union of Geological Sciences van 20 maart 2024 klinkt het zo:

Some have pointed to the fact that anthropogenic effects on the Earth’s environmental and climate systems long predate the mid 20th century (e.g. early agriculture; the industrial revolution in western Europe, the colonisation of the Americas and Pacific, etc.) and hence the Anthropocene has much deeper roots in geological time.3

Ten eerste ligt het al eerder vermelde misverstand dus aan de basis van de afwijzing: het gaat immers niet over de menselijke invloed op de planeet per se, maar over het feit dat de planeet door menselijke impact in een nieuwe instabiele toestand is gebracht, en dat tegenover de relatieve stabiliteit van het holoceen.

Een tweede argument voor de verwerping was de zogenaamde recency bias. In de geologische tijd is de twintigste eeuw vergeleken met een menselijke tijdsbeleving een seconde geleden. In het statement van 20 maart 2024 geeft de International Union of Geological Sciences dat aan als een van de punten van kritiek: “Others have expressed unease about a new unit in the GTS [Geological Time Scale] that truncates the Holocene but with a span of less than a single human lifetime, it sits uncomfortably within the GTS where the units span thousands or even millions of years.” 4 De radicale keuze voor het meeste recente en meest duidelijke fenomeen van de Grote Versnelling zou wel eens het doodsvonnis hebben kunnen tekenen van deze veelbelovende, uitdagende term.

Een ander nadeel van het ijkpunt was ook dat men een plek heeft moeten kiezen. Het werd, zoals gezegd, Lake Crawford in Canada. Een derde argument tegen het antropoceen als geologische periode is daarom dat het gaat om in tijd en ruimte verspreide ongelijke effecten: “the effects on global systems are time-transgressive and are also spatially and temporally variable, so that their onset cannot be adequately represented by an isochronous horizon as reflecting a single point in time.”5

Het alternatief leek daarom dat het antropoceen geen geologisch tijdperk is, maar een gebeurtenis:

An alternative narrative has therefore arisen in which the Anthropocene is not considered as a series/epoch (i.e., a chronostratigraphic unit and the corresponding geochronologic unit) but rather as an event, similar to the great transformative events in Earth history such as the Great Oxygenation, the Cambrian Explosion, or the Great Ordovician Biodiversification events. None of these major transformative events in Earth history are represented as chronostratigraphic units, and hence there has been no requirement for formal ratification. If so, the Anthropocene could be considered as an informal non-stratigraphical term.6

Dat lijkt een ontsnappingsroute om de term nog een kans te geven: niet als tijdperk maar als gebeurtenis of proces. Maar dan is de term niet adequaat, precies omdat die een tijdperk suggereert, door zijn lexicale vorm: holoceen, antropoceen. In elk geval haalt dat de angel uit het begrip: de invloed van de mens is zo oud als… de mensheid. Dus geen zorgen. Volgens betrokkenen was de verwerping in elk geval een misverstand: het ging immers niet over de impact van de mens op de planeet, want die was oud en bekend, maar het feit dat de mens het stabiele tijdvak van het holoceen onderbrak en de planeet in een nieuwe instabiele toestand bracht.7

De International Union of Geological Scientists probeerde de verwerping van de term aan het einde van het statement, na een vrij pijnlijke beschrijving van het stemmingsproces, een positieve draai te geven:

Despite its rejection as a formal unit of the Geologic Time Scale, Anthropocene will nevertheless continue to be used not only by Earth and environmental scientists, but also by social scientists, politicians and economists, as well as by the public at large. It will remain an invaluable descriptor of human impact on the Earth system.8

Dat argument werd breed overgenomen.9 De tijd zal moeten uitwijzen of de term nog een toekomst heeft. De kans is echter groot dat de verwerping relatief fataal zal blijken te zijn geweest. Men kan nu al vaststellen dat de term al wat minder op de voorgrond treedt in de media. Hij was bezig om breed zichtbaar te worden, maar dat lijkt nu al voorbij en men kan voorspellen dat de term verder zal wegdeemsteren. Men kan de schouders ophalen en het afdoen als een typisch modeverschijnsel in de theorievorming. Er komt wel weer een andere term. Maar er is een verschil: het holoceen was geen modeverschijnsel.

De term was nochtans veelbelovend, juist omdat hij vanaf het begin ook heel controversieel was. In een soort van creatief tegenoffensief werd een hele reeks tegentermen gelanceerd. Veruit de belangrijkste kritiek bestond erin dat niet ‘de mensheid’, maar het kapitalisme verantwoordelijk was voor de destabilisering van de biosfeer. Vandaar dat T.J. Demos een pamflet schreef tegen het concept antropoceen.10 Anderen kwamen met alternatieve termen. De belangrijkste was wellicht ‘Capitalocene’, een term voorgesteld door milieuhistoricus Jason Moore en overgenomen door ecofeministen als Donna Haraway.11 Haraway deed er nog een schepje bovenop door de nogal frivole term ‘Chthulucene’ te lanceren, dat naar een chtonisch, veelarmig wezen en zo naar de aardkrachten moest verwijzen. Ze wilde daarmee een tegenterm naar voren schuiven die de ecofeministische kritiek moest overbrengen dat het antropoceen van een kolonialistisch machistisch antropocentrisme getuigde. De geschiedenis werd gezien als triomftocht van het extractivistische, koloniale kapitalisme en van de patriarchale ‘Mankind’ (de menselijke soort als samenvallend met het mannelijke deel), dat de vrouwelijke moederaarde, Gaia, onderdukt en uitbuit.

Er waren ook ernstigere termen zoals ‘plantationocene’ van Anna Tsing, die het koloniale systeem van monocultuur met de vinger wees.12 Verder was er ook nog, in de lijn van Lyn Margulis, het ‘symbioceen’ als tegenbeeld van het antropoceen: niet de mens, maar de symbiose moest centraal worden gesteld en de mens gedecentreerd als deel van dat grote symbiotische systeem binnen Gaia. Juist omwille van die rijkdom aan theorievorming en discussie, proberen nu een aantal academici in lijn met het vertoog van de International Union of Geological Scientists, de beroering over het verwerpen van de term te sussen door te stellen dat de term nu voluit zijn rol als culturele term kan vervullen.

Dat valt ten zeerste te betwijfelen. Een geologisch tijdperk dat er geen is, slaat nergens op. De term wordt onbruikbaar. Jammer, maar helaas. De mensen die hebben gegokt dat het voorstel waaraan vijftien jaar onderzoek is gewijd, het zou halen, hebben zich vergist.13 De term is gedemodeerd, nutteloos geworden, alleen nog interessant als verzamelterm voor een discussie: het ‘antropoceendebat’, een beetje vergelijkbaar met het ‘postmodernismedebat’ in de jaren tachtig van de vorige eeuw. Hoewel alle vergelijkingen mank lopen en er grote verschillen bestaan tussen beide termen, zijn er toch ook sterke gelijkenissen: beiden waren pogingen om het heden te vatten en te benoemen. Beide waren pogingen om kritisch terug te blikken op de moderniteit. En er is nog een verwantschap: het gaat om het twijfelen aan vooruitgang, de ultieme grondterm van de moderniteit en van alle modernismen. Jean-François Lyotard maakte een rapport over de toestand van kennis, waarin hij het einde van de ‘grote verhalen’ over vooruitgang en emancipatie, kern van de moderniteit, vaststelde.14

Omdat het woord antropoceen lexicaal vastzit aan de geologie, zichzelf als geologisch tijdperk presenteert door de uitgang -ceen (nieuw tijdperk), kan je de term, omdat die dus geen geologisch tijdperk is geworden, enkel nog tussen aanhalingstekens gebruiken. Wellicht moeten we op zoek naar andere termen.

De fataliteit van de Grote Versnelling

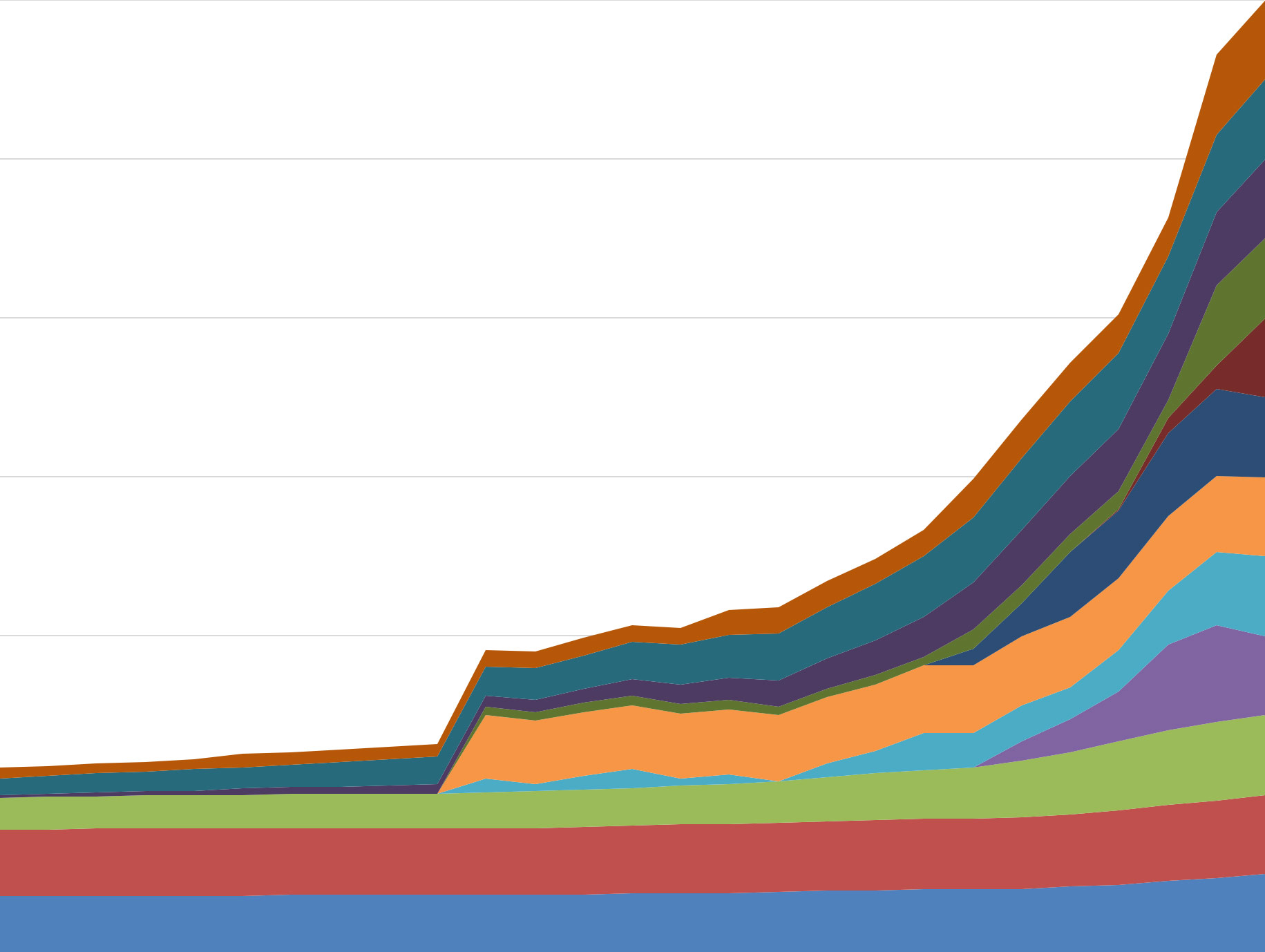

In het zog van de zoektocht naar het begin van het antropoceen, werd het fenomeen van de Grote Versnelling ‘ontdekt’. De term ‘Grote Versnelling’ werd ingevoerd in 2004 door een groep wetenschappers onder leiding van Will Steffen in het kader van het International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme, en dat als directe respons op de oproep van Crutzen om de term antropoceen te onderbouwen. Maar in tegenstelling tot Crutzen die het begin van het antropoceen situeerde bij de industriële revolutie en als ijkpunt verwees naar de uitvinding van de stoommachine, stelden ze tot hun verbazing vast dat pas vanaf 1950 alle parameters een steile groei vertoonden. Dit fenomeen werd dus weldra de Grote Versnelling genoemd in de groep en in 2005 werd er voor het eerst over gepubliceerd. Het was juist het op hol slaan van alle parameters dat de variabiliteit binnen het holoceen verbrak en de aarde in een nieuwe instabiele toestand bracht – en dus het juiste beginpunt leek voor een nieuw geologisch tijdperk.

Vanaf omstreeks 1950 begonnen twaalf parameters van socio-economische factoren en twaalf parameters van effecten ervan op het milieu aan een steile klim, dit door het zogenaamde ‘Wirtschaftwunder’ en het Marshallplan dat een grote technologische en economische groei realiseerde, kortom door de heropbouw en heropleving na het einde van de Tweede Wereldoorlog. Meestal ging het om exponentiële groei, wat er in de grafische weergave als een boog die alsmaar verticaler wordt uitziet. De socio-economische factoren zijn relatief bekend: allereerst is er de bevolkingsexplosie,15 uiteraard ook ‘real GDP’: de economische groei was fenomenaal. ‘Foreign Investment’ is een goede graadmeter voor globalisering. De volgende parameter is ‘urban population’, oftewel de urbanisering van de mensheid. Vervolgens energieverbruik, dat zo de pan uit swingt dat alle hernieuwbare energie alleen dient om de bijkomende vraag bij te benen en het verbruik van fossiele brandstoffen toch ook nog doet groeien… Waterdammen en papierconsumptie spreken wat minder tot de verbeelding, maar de exponentiële groei van telecommunicatie en transport spreken dan weer boekdelen over de globalisering. De explosie van het toerisme lijkt een leuke voetnoot en de laatste parameter, namelijk technologie, een soort van truïsme: de technologische revolutie lijkt wel permanent te worden sinds het midden van de vorige eeuw.

Een tweede reeks grafieken van de ‘Earth systems’ toont de gevolgen: de uit de hand gelopen CO2-uitstoot staat op nummer 1, gevolgd door de twee andere broeikasgassen, stikstof en methaan. Dat laatste vertoont recent een lichte daling. Dan komt de stratosferische ozon, die na een steile stijging vrij stabiel is (door het bannen van koelstoffen, de zogenaamde CFK’s). De oppervlaktetemperatuur blijft stijgen en is de directe indicator van de klimaatopwarming. De verzuring van de oceanen door de opname van koolstofdioxide blijft alarmerend stijgen, met fatale gevolgen voor de koraalriffen. De visvangst lijkt over zijn hoogtepunt heen, omdat er gewoon minder vis is door overbevissing. De aquacultuur van garnaalsoorten vertoont een scherpe stijging om het tekort aan vis te compenseren. Ook de toename van stikstof in de kustwateren blijft gestaag doorgaan, waar alweer de koraalriffen het slachtoffer van zijn. Het verlies aan tropisch bos blijft onverminderd doorgaan, terwijl de domesticatie van land iets minder snel gaat, simpelweg omdat er geen bewerkbaar land meer over is, of het moet ten koste gaan van de bossen. Ten slotte op nummer twaalf is er de blijvende stijging van de degradatie van de biosfeer, of een sterke afname van biodiversiteit, ook bekend als ‘de zesde grote uitsterving’.16

Het ongemeen sterke van deze opstelling bestaat erin dat die twee lijsten van grafieken samen een visuele voorstelling geven van de ongebreidelde, fenomenale groei sinds 1950 en zwart op wit tonen dat dit een ecologische catastrofe is. De berekeningen van de grafieken werden op gezette tijden verder verfijnd en bevestigd. In een tekst uit 2015 heet het nog vol vertrouwen:

Only beyond the mid-20th century is there clear evidence for fundamental shifts in the state and functioning of the Earth System that are beyond the range of variability of the Holocene and driven by human activities. Thus, of all the candidates for a start date for the Anthropocene, the beginning of the Great Acceleration is by far the most convincing from an Earth System science perspective.17

Dat argument bleek dus niet overtuigend voor de geologen. Men zou ook kunnen stellen dat het een strijd van wetenschappen is, omdat de term antropoceen eerder uit de ecologie en biosfeerwetenschappen komt en de geologen letterlijk en figuurlijk koud liet. In de geciteerde passage waarin Crutzen en Stoermer de term antropoceen introduceerden, is het, zoals we reeds aangaven, symptomatisch dat geologie en ecologie in één adem worden genoemd, terwijl zowat alle evidentie om te spreken over het antropoceen, ook die in het oorspronkelijk artikel, veel meer ecologisch is dan geologisch. Dat geldt ongetwijfeld ook nog voor de Grote Versnelling. In de geologie zijn grootschalige catastrofale fenomenen meer regel dan uitzondering. Maar dat belet niet dat de Grote Versnelling een sterk concept op zich is, dat een synthetisch beeld geeft van de fatale processen die zich voor onze ogen afspelen.

Omdat stad en architectuur een van onze specifieke velden van interesse vormt, ga ik even dieper in op de urbanisering van de mensheid. In de reeds geciteerde basistekst over de Great Acceleration klinkt het:

One of the most important trends of all is the rapid rate of urbanisation. The move from rural to urban living began its contemporary rise in the late 1800s and its rate has steadily increased since then, rising more sharply around 1950 and continuing to the present. About 2008 humanity passed a historic milestone: over 50% of the global population now live in urban areas. On current trajectories there will be more urban areas built during the first three decades of the 21st century than in all of previous history combined.18

Verder stellen de auteurs terecht dat de vorm van urbanisering cruciaal zal blijken: “In a practical sense, the future trajectory of the Anthropocene may well be determined by what development pathways urbanisation takes in the coming decades, particularly in Asia and Africa.” Daaruit blijkt dat het vormgeven van het stedelijke leven, zowel van bovenaf (stadsplanning en beleid) als van onderuit (stadsactivisme), de toekomst van de planeet mee zullen bepalen.

Interessant is ook dat in de tekst van 2015 de grafieken zijn uitgesplitst, zodat het aandeel en dus ook de verpletterende verantwoordelijkheid van de rijke landen zichtbaar wordt. Dit was een uitdrukkelijk antwoord op de kritieken dat de term antropoceen de hele mensheid de schuld leek te geven. Nog belangrijker is dat het verhaal van de groene groei in de geüpdatete tekst over de Grote Versnelling van Will Steffen en zijn collega’s als leugen ontmaskerd wordt: “The rise in carbon dioxide concentration parallels closely the rise in primary energy use and in GDP, showing no sign yet of any significant decoupling of emissions from either energy use or economic growth.”19 Tussen 2000 en 2010 waren er geen tekenen van beterschap wat betreft CO2-uitstoot. Kortom: doordat we gevangen zitten in de logica van de groei, gaan we los over de planetaire grenzen. Dat dit niet straffeloos kan, bewijst het intensifiëren van ‘extreme weerfenomenen’, zoals lange periodes van droogte, hittegolven, bosbranden, megastormen, waterbommen met verwoestende overstromingen als gevolg, maar ook stille rampen zoals het smelten van de gletsjers en het stijgen van de zeespiegel door het smelten van de ijskappen in de Poolgebieden.

Planetaire grenzen

Verder denkend op het befaamde rapport van de Club van Rome uit 1972, met zijn iconische titel Limits to Growth, ontwikkelde het Stockholm Institute for Resilience, ongeveer in dezelfde periode en in dezelfde geest, de term Planetary Boundaries om de grensoverschrijdingen te kunnen preciseren en meten. Op de website van het instituut staat het volgende:

In September 2023, a team of scientists quantified, for the first time, all nine processes that regulate the stability and resilience of the Earth system. These nine Planetary Boundaries were first proposed by former centre director Johan Rockström and a group of 28 internationally renowned scientists in 2009. The Planetary Boundaries are the safe limits for human pressure on the nine critical processes which together maintain a stable and resilient Earth. The 2023 update not only quantified all boundaries, it also concluded that six of the nine boundaries have been transgressed.20

Deze negen planetaire grenzen komen grosso modo overeen met de twaalf ‘Earth Systems’-grafieken in de theorie van de Grote Versnelling, maar leggen toch andere accenten. De eerste grens betreft klimaatverandering door broeikasgassen en aerosols – en die grens is overschreden. Dan zijn er novel entities (chemische pollutie, microplastics, en dergelijke), waarvan de hoeveelheid de veilig grens eveneens overschreden heeft. De derde grens betreft stratosferische ozon. Dat probleem is voor een groot stuk opgelost en dus binnen veilige grenzen. Vier: de concentratie van atmosferische aerosols, d.i. fijn stof dat ook neerslag beinvloedt, blijft ook nog binnen redelijk veilige grenzen. Vijf: verzuring van de oceanen door opname van CO2 is nefast voor het leven in zee en maakt verdere CO2-opslag moeilijker. We zijn dicht bij het overschrijden van deze grens. De zesde grens is de modificatie van biochemische processen, vooral door stikstof en fosfor, die het milieu uit evenwicht brengen. Die grens hebben we overschreden. Ook wat betreft watercycli, de zevende grens, hebben we het veilige niveau van menselijke interventie overschreden:

The alteration of freshwater cycles, including rivers and soil moisture, impacts natural functions such as carbon sequestration and biodiversity, and can lead to shifts in precipitation levels. Human-induced disturbances of both blue water (e.g. rivers and lakes) and green water (i.e. soil moisture) have exceeded the safe level.

De achtste grens heet Land System Change, of gebruik van land. Op dat vlak blijkt vooral ontbossing allang de veilige grenzen te hebben overschreden. Last but not least is er ‘Biosphere Integrity’:

The diversity, extent, and health of living organisms and ecosystems affects the state of the planet by co-regulating the energy balance and chemical cycles on Earth. Disrupting biodiversity threatens this co-regulation and dynamic stability. Both the loss of genetic diversity and the decline in the functional integrity of the biosphere are outside safe levels.21

Dit is dus overduidelijk een heel slecht rapport. Heel alarmerend.

Maar wat zijn nu de criteria voor de bepaling van planetaire grenzen? In het oorspronkelijke wetenschappelijke artikel uit 2009 waarin de term ‘Planetary boundaries’ werd geïntroduceerd, schreven de auteurs: “we present a novel concept, planetary boundaries, for estimating a safe operating space for humanity with respect to the functioning of the Earth System”.22 De planetaire grens moet dus een veilige werk- of speelruimte bepalen waarbinnen de mensheid kan opereren.

En wat is dan deze veilige speelruimte voor de mensheid? Alles wat die onaanvaardbare wereldwijde ecologische verandering in het systeem aarde vermijdt: “the boundary level that should not be transgressed if we are to avoid unacceptable global environmental change.” En die onaanvaardbare grens wordt nader bepaald: “Unacceptable change is here defined in relation to the risks humanity faces in the transition of the planet from the Holocene to the Anthropocene.” Alweer is het antropoceen hier het kader en de ultieme referent voor de destabilisering van de aardsystemen: “we must take the range within which Earth System processes varied in the Holocene as a scientific reference point for a desirable planetary state.” Ze laten er geen twijfel over bestaan dat dit de norm moet zijn voor het antropoceen.

De eeuw van de Grote Versnelling?

Onze korte toelichting van beide nieuwe termen heeft ons geleerd dat zowel de Grote Versnelling als Planetaire Grenzen zijn gemunt met directe referentie naar het antropoceen. Dat betekent dat het concept een sterke heuristische functie heeft gehad, een epistemologische zoekterm is geworden, een drijfveer achter onderzoek naar en conceptualisering van de ecologische toestand van de planeet aarde. Dat is, achteraf beschouwd, een grote verdienste van de nu begraven term.

Maar er zijn ook nadelen. Dat “planetaire speelveld voor de mensheid” doet uiteindelijk toch vragen rijzen. Men kan zich, met de ecofeministische kritiek op het antropoceenbegrip in het achterhoofd, afvragen of beide terminologieën niet uiteindelijk nog altijd getuigen van het technocratische antropocentrisme van de positieve wetenschappen, die ‘de mens’, of althans het kapitalisme, zoveel mogelijk manoeuvreerruimte willen geven, en uiteindelijk een trots uitstralen over die Grote, lees Grootse Versnelling. Het wetenschappelijke paradigma van waaruit de termen zijn gesmeed, blijft kennelijk geloven dat wetenschap en technologie de oplossing kunnen brengen, zonder systeemverandering. De vraag is of beide termen dus niet eerder passen binnen een agenda van accelerationisme: we moeten eerder inzetten op slimme groene technologie dan op vertraging en degrowth. Dat laatste is volgens velen in de klimaatbeweging de enige oplossing, of althans de enige manier om op korte termijn het allerergste, een opwarming van meer dan 3 tot 5 graden met alle kantelpunten die daarbij horen, te vermijden. Dat is de zogenaamde Hothouse Earth-hypothese, geformuleerd door een groep wetenschappers onder leiding van diezelfde Will Steffen.23 Als we niet snel ingrijpen, kan de opwarming tot 5 graden oplopen, wat het einde zou betekenen van de meeste ecosystemen en zelfs van meeste hogere levensvormen op de planeet aarde.

Nu we de term antropoceen als een lege huls achter ons moeten laten - misschien met spijt in het hart -, moeten we zoeken naar nieuwe termen. Misschien zouden we kunnen spreken van de Eeuw van de Grote Versnelling. Tussen 1950 en 2050 zal zich een explosieve ontwikkeling hebben voorgedaan, gebaseerd op de exponentiële groei van zowel economische als ecologische parameters. Er zal zich naast geweldige verwezenlijkingen een gigantische ecologische catastrofe hebben voorgedaan, met de klimaatchaos en de zesde grote uitsterving sinds het bestaan van de planeet als meest bekende. Het voordeel van spreken over de eeuw van de Grote Versnelling, is de neutraliteit of ambivalentie van de term: zowel de ongebreidelde groei als zijn catastrofale effecten worden in één visueel beeld gebracht.

Is het einde van de Grote Versnelling in zicht? Dat lijkt niet het geval, als je een blik werpt op de volop aan de gang zijnde AI-revolutie. Tegelijk staat het in de sterren geschreven dat eindeloze groei in een eindig systeem niet houdbaar is. Tegen 2050 zouden we een einde van de Grote Versnelling kunnen voorspellen. Dat klinkt vredig en hoopgevend, maar kan even goed verschrikkelijk en apocalyptisch zijn. Wellicht wordt de tweede helft van de eenentwintigste eeuw een uiterst chaotische periode, met zowel sociale, politieke, economische als ecologische ellende, met naast extreme weerfenomenen ook een metastase van politieke extremismen. We staan aan het begin van het fin de siècle van de Grote Versnelling. Zoals het fin de siècle van de negentiende eeuw: een tijdperk van de decadente verspilling en ook het tijdperk van Grote Verwarring, posthruth, alternatieve feiten met een epidemie van samenzweringstheorieën.

Een andere naam voor ons tijdperk zou daarom ook kunnen zijn: het tijdperk van de ineenstortingen. Het meervoud zou kunnen suggereren dat het over verscheidene processen gaat, wat intussen met de term ‘polycrisis’ wordt aangeduid: de ineenstorting van het stabiele klimaat van het holoceen, de ineenstorting van de biodiversiteit, de ineenstorting van de democratie, de ineenstorting van de internationale rechtsorde, de ineenstorting van de globalisering.

De termen van de Grote Versnelling en de Planetaire Grenzen leveren wat dat betreft een graadmeter. Toen die laatste terminologie werd ingevoerd in 2009, waren er drie van zeven planetaire grenzen overschreden, in 2023 waren dat er al zes. Met aan wetenschappelijke zekerheid grenzende waarschijnlijkheid staat ons een tijdperk van voorspelde en voorspelbare catastrofes, ontzettend veel ellende en ongekende chaos te wachten.

Noten:

- 1 Paul J. Crutzen and Eugene F. Stoermer, “The Anthropocene”, in: Global Change Newsletter, 41 (2000): 17-18. Zie ook Max Planck Institute: https://www.mpic.de/3865097/the-anthropocene

- 2 “Orbis spike” is een allusie op de eenwording van de wereld door de ontdekking van beide Amerika’s. Het ijkpunt betreft de geologische sporen van de herbebossing van de beide Amerika’s als gevolg van de massale sterfte van de inheemse bevolking (een daling met naar schatting 50 miljoen), veroorzaakt door de kolonisering, en de daarmee gepaarde gaande ziektes, geweld en uitbuiting. Voor meer info, zie https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orbis_spike

- 3 International Union of Geological Sciences, “The Anthropocene”, https://www.iugs.org/_files/ugd/f1fc07_ebe2e2b94c35491c8efe570cd2c5a1bf.pdf

- 4 Ibid.

- 5 Ibid.

- 6 Ibid.

- 7 Simon Turner, “Analysis: What the Anthropocene’s critics overlook and why it should be a new geological epoch”, UC News, 12 March 2024, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2024/mar/analysis-what-anthropocenes-critics-overlook-and-why-it-should-be-new-geological-epoch

- 8 Ibid.

- 9 Zie o.a. Lou Sherry, “Not Yet Anthropocene: What the Official Rejection of Earth’s New Epoch Means for the Climate Discourse”, Earth.Org, https://earth.org/not-yet-anthropocene-what-the-official-rejection-of-the-anthropocene-as-earths-new-epoch-means-for-the-climate-discourse/

- 10 T.J. Demos, Against the Anthropocene. Visual Culture and the Environment Today. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2017.

- 11 Jason W. Moore, The Capitalocene, Part I: On the Nature and Origins of our Ecological Crisis. London: Taylor & Francis, 2017; Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. London: Duke University Press, 2016.

- 12 Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World. On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

- 13 Inclusief schrijver dezes, wiens boek Ending the Anthropocene. Essays on Activism in the Age of Collapse (NAi010, 2021) nu een soort van anachronistische, voorbijgestreefde titel draagt. Dit artikel is aangedreven door die bittere vaststelling.

- 14 Jean-François Lyotard, La condition postmoderne. Rapport sur le savoir. Paris: Minuit, 1979.

- 15 In 1960 waren er drie miljard mensen op aarde; nu zijn we onderweg naar de negen miljard. Dat betekent dat we (ik bijvoorbeeld) in een mensenleven de verdriedubbeling van de mensheid aan het meemaken zijn.

- 16 Voor een eerste kennismaking met deze zwaar onderschatte ecologische catastrofe, zie: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holocene_extinction

- 17 Will Steffen, Wendy Broadgate e.a., “The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration”, The Anthropocene Review, 2015, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2053019614564785

- 18 Ibid.

- 19 Ibid.

- 20 Stockholm Resilience Centre, “Planetary Boundaries”, https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/planetary-boundaries.html

- 21 Ibid.

- 22 Johan Rockström, Will Steffen e.a., Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity, in: Ecology and Society, 14.2 (2009), http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss2/art32/

- 23 Will Steffen, Johan Rockström e.a., “Trajectory of the Earth System in the Anthropocene”, PNAS 115.33 (2018),https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1810141115